Stop Calling Melinda Wang "Matt Reeves's Wife"

Melinda Wang is an accomplished animator who worked on several beloved films, yet she is often referred to as "Matt Reeves's wife." In the animation industry, that is only the tip of the iceberg.

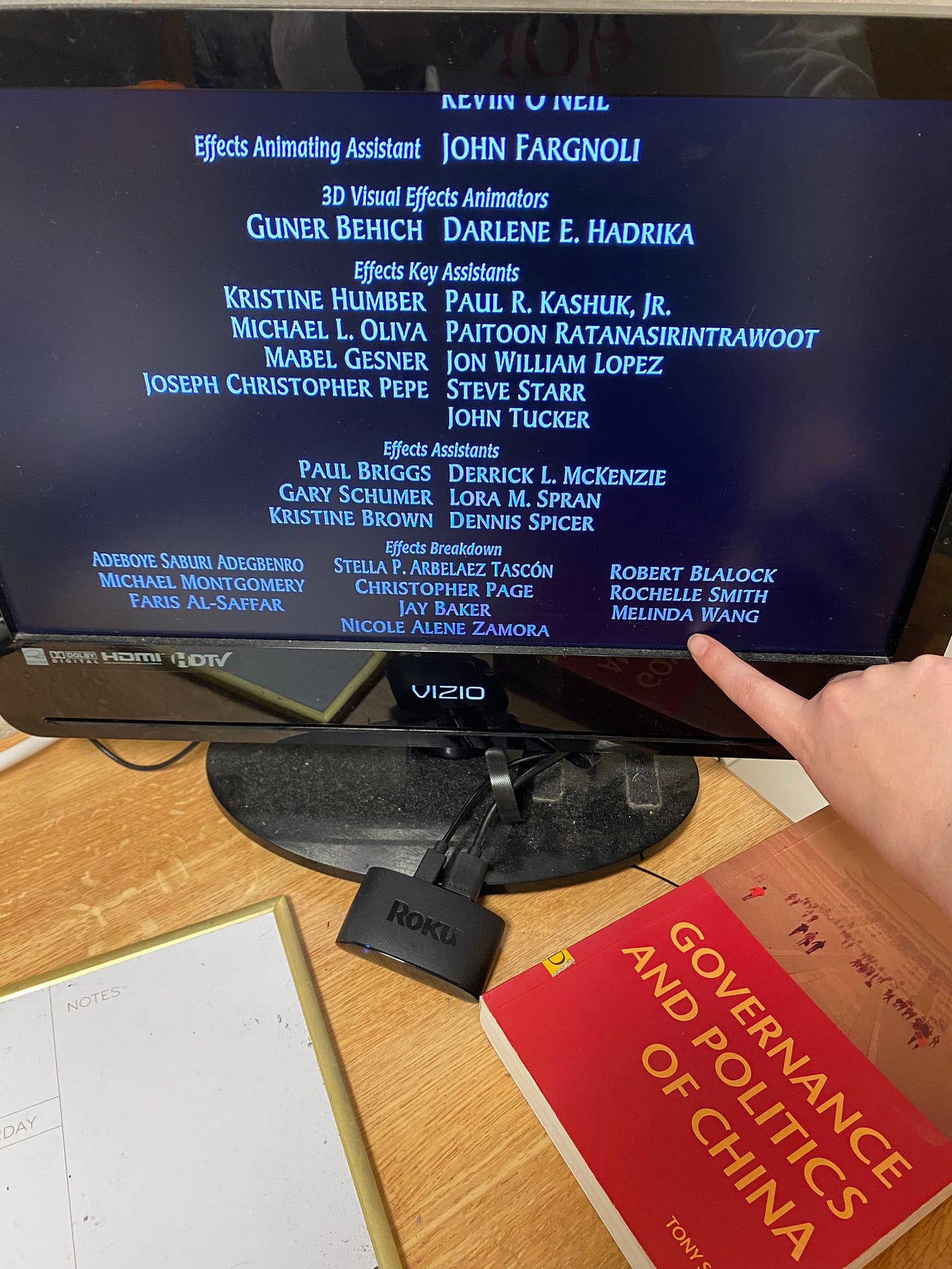

Animator Melinda Wang has a stellar resume, to say the least. According to her IMDb page, Wang worked on visual effects for films such as Mulan, Hercules, Atlantis: The Lost Empire, and Meet the Robinsons.

She is also married to film director Matt Reeves. Wang and Reeves are often seen together at the latter’s premieres, like at the 2019 premiere for his production company 6th & Idaho’s television series The Passage:

While she is a private person, Reeves has occasionally mentioned his spouse in interviews; during a roundtable for Dolby’s Sound and Image Lab podcast, he talked about Wang’s reaction to the Batmobile chase scene in The Batman (2022). “My wife just saw the movie, we had a little screening,” Reeves said. “When that moment happens when the car goes [vroom], she [jumped.]”

Yet, she is often reduced to her personal life. Despite her accomplishments in the animation industry, one wouldn’t know about her professional career without committing to deep research. Wang’s former occupation was vaguely mentioned in a 2014 Wall Street Journal profile of Reeves.

If the roles were reversed (her being the director, him being the animator), would Matt Reeves be “Melinda Wang’s husband?” Would his career be acknowledged? In a town like Hollywood, there are easy answers to those questions.

Wang’s narrative is not an isolated case. Women like human rights lawyer Amal Clooney, Oscar-nominated producer Emma Thomas, and art curator Gisele Schmidt have been reduced to being George Clooney, Christopher Nolan, and Gary Oldman’s wives respectively.

Additionally, Wang’s case speaks volumes about the animation industry, where animators — especially women and people of color — are rarely acknowledged. She is not alone regarding the lack of recognition for animators. Over the past several years, the industry has been riddled with sexual misconduct allegations against animation powerhouses such as former chief creative officer for PIXAR John Lasseter and The Ren and Stimpy Show creator John Kricfalusi.

It is time we acknowledge the hard work of animators. One way we can do that? Emphasize Melinda Wang the former animator, not Melinda Wang the wife.

Reflection

Many people do not know Wang’s background in animation. I only learned about her career after doing some research relating to Reeves (to be fair, I am a foreign affairs major, and we have a knack for research.)

It wasn’t until I made a tweet that I learned just how much Wang’s professional background had been unknown. After I was accepted to Virginia Tech as a transfer student, I celebrated by watching Mulan. Before you ask: yes, I watched it because of Wang’s involvement:

To my surprise, it was mindblowing for people who were unaware of Wang’s work. There was the notion, “It’s a small, small world!” Why was this the case? Why is her work not “significant” in her narrative? After some self-reflection, I realized I played a role in Wang’s work fading into the background.

I run a Twitter fan account for Reeves, where I regularly post updates, fun facts, and content about the director. Sometimes, the updates I post happen to feature Wang.

What I noticed was my wording: I always said, “Matt Reeves and his wife, former animator Melinda Wang…” It was never worded as, “Matt Reeves and former animator Melinda Wang — his wife —”

His wife.

Amidst sharing my love for a favorite director of mine and his work, I ultimately took Wang’s independence. She was merely his wife, and the rest wasn’t necessary.

That epiphany amplified while watching Mulan — a movie about a girl learning how to define herself. Mulan adapts to a man’s world, yet her identity becomes the key to saving China and stopping Shan Yu.

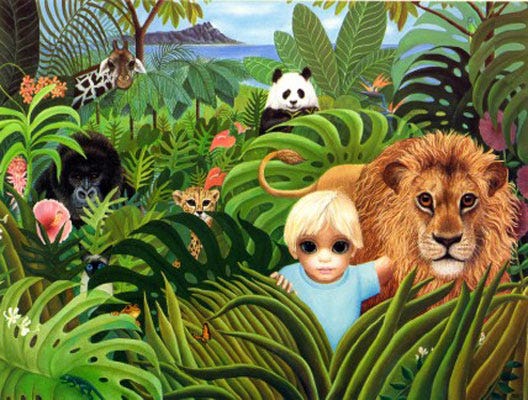

Female artists like Wang have to work harder to make a dent in the art world. It is a tale as old as time — just ask the Margaret Keane print in my dorm.

The Windows of the Soul

Margaret Keane’s paintings served as the primary inspiration for the design of the leads in Craig McCracken’s cartoon series The Powerpuff Girls. Her influence is evident throughout the series, including Pokey Oaks Kindergarten’s beloved teacher Miss Keane.

While her kitschy paintings are praised, her career wasn’t always a fairytale.

Margaret Keane often referred to eyes as being “the windows of the soul.” She wanted to illustrate those eyes through a vivid combination of oil strokes. Keane’s paintings were adored by many, including actress Natalie Wood. The only problem? They were praising the wrong Keane.

During her abusive marriage to Walter Keane, he took credit for her work. Art galleries and festivals around the world celebrated Walter Keane’s paintings — except, it wasn’t his work. Other than Walter’s signature on the paintings, it was Margaret who painted the sad little girls with doe eyes.

After escaping her marriage and obtaining sole custody of their daughter, Margaret told the truth about the “big eyes” paintings on a radio show in Hawaii. When Walter denied Margaret’s allegation and attacked her credibility, she sued him for defamation. Following a lengthy court battle and a paint-off ordered by the judge, a jury ruled in favor of Margaret after she painted a portrait in thirty minutes. Walter — who sat out of the paint-off, citing a sore arm — died broke and scorned.

If her story sounds familiar, it is the subject of the film Big Eyes (2014) dir. Tim Burton. Starring Amy Adams as Margaret Keane, the movie resulted in a resurgence of Keane’s paintings.

The portfolio of Margaret Keane can be best described as an autobiography. After a period in which her paintings depicted gloomy little girls (re: during her marriage to Walter), her work became upbeat following her vindication.

Margaret Keane’s story inspired future generations of female artists like Melinda Wang. For some artists, nonetheless, that story can also be a flat circle.

Drawing the Line

Author’s note: This section contains detailed descriptions of sexual violence which may be triggering for some readers.

The National Sexual Assault Hotline is available at 1-800-656-4673.

Since the #MeToo movement, disturbing stories of predatory behavior have surfaced in the animation industry. Most of these stories have a pattern: young aspiring artists — most of whom are female — get taken advantage of by powerful men in animation.

When sexual harassment allegations against former PIXAR chief creative officer John Lasseter surfaced in The Hollywood Reporter, it exposed how his behavior was swept under the rug at PIXAR.

“Sources say some women at Pixar knew to turn their heads quickly when encountering him to avoid his kisses,” journalist Kim Masters writes. “Some used a move they called ‘the Lasseter’ to prevent their boss from putting his hands on their legs.”

One insider at PIXAR provides the extent of Lasseter’s open secret. Masters reports:

A longtime insider says he saw a woman seated next to Lasseter in a meeting that occurred more than 15 years ago. “She was bent over and [had her arm] across her thigh,” he says. “The best I can describe it is as a defensive posture … John had his hand on her knee, though, moving around.” After that encounter, this person asked the woman about what he had seen. “She said it was unfortunate for her to wear a skirt that day and if she didn’t have her hand on her own right leg, his hand would have traveled.”

The same source said he once noticed an oddly cropped photo of Lasseter standing between two women at a company function. When he mentioned that to a colleague, he was told, “We had to crop it. Do you know where his hands were?”

Lasseter is not the only predator in animation who has been outed, nor will he be the last.

A few months after Lasseter took a leave of absence from PIXAR (he now runs a production company specializing in animation), an article in BuzzFeed News detailed allegations of underage sexual abuse against The Ren & Stimpy Show creator John Kricfalusi. Ariane Lange reports on one victim of Kricfalusi, Robyn Byrd:

When she was still in 11th grade, [Kricfalusi] flew her to Los Angeles to show her his studio and talk about her future. She said that on the same trip, in a room with a sliding glass door that led to his pool, he touched her genitals through her pajamas as she lay frozen on a blanket he’d placed on the floor. She was 16.

It didn’t end there. In the summer of 1997, Byrd moved in with Kricfalusi as his 16-year-old girlfriend and intern at his animation studio. Kricfalusi’s grooming was so well known in the animation industry, that a book about the history of Ren & Stimpy briefly mentioned “a girl [Kricfalusi] had been dating since she was fifteen years old” as a casual anecdote. Byrd wasn’t the only girl groomed by Kricfalusi; another survivor, Katie Rice, detailed his behavior:

Although Kricfalusi never had a physical sexual relationship with Rice, he began hitting on her when she was a minor, she said, behavior that ranged from writing her flirty letters (“I bet you’ll be up to no good. Just like me,” he wrote in 1996) to masturbating while she was on the phone. In 2000, when Rice was 18 and trying to break into animation, Kricfalusi offered her a job. Once she started working for him, Rice said, he persistently sexually harassed her.

Nickelodeon had a portrait of Kricfalusi hanging on their walls; despite his well-known predation, his portrait was only removed after the BuzzFeed article was published.

Even after this historic reckoning, there are still Lasseters and Kricfalusis roaming in the animation industry. How can we make the industry better?

Pragmatically speaking, it is hard to reform an industry on the outside. Yet, outsiders can also take little steps to address sexism in the animation industry. One step we can take? Acknowledging Melinda Wang beyond her personal life.

Knowing her movies, watching her movies, and recognizing Wang outside of her husband’s narrative can make a small but important impact.

It’s time we start highlighting Melinda Wang the former animator.